West Nile virus: A Q&A with Dr. Mark Loeb

Reported cases of West Nile virus in parts of Southern Ontario has led public health officials from across the province to ask the public to take extra precautions against mosquito bites.

Dr. Mark Loeb, a professor in the Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine and a member of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, offers some valuable advice on how to stay protected from this end-of-summer scourge.

Who’s most at risk for getting West Nile?

Age is a real important risk factor. Children can be infected with West Nile, but they typically don’t get severe complications. Those most at risk for complications are people who are middle-aged or older. Complications include meningitis, encephalitis, and acute flaccid paralysis – a condition often characterized by muscle weakness and, in some cases, paralysis of a limb.

In terms of risk factors, generally, they’re not well defined in the literature. There are some studies that suggest that people who are on immunosuppression drugs might be at risk of complications. Other studies suggest that those with hypertension are at risk, too.

When is West Nile most prevalent?

Now is the time. Essentially, exposure to mosquitoes that are infected with West Nile goes up in late August, early September.

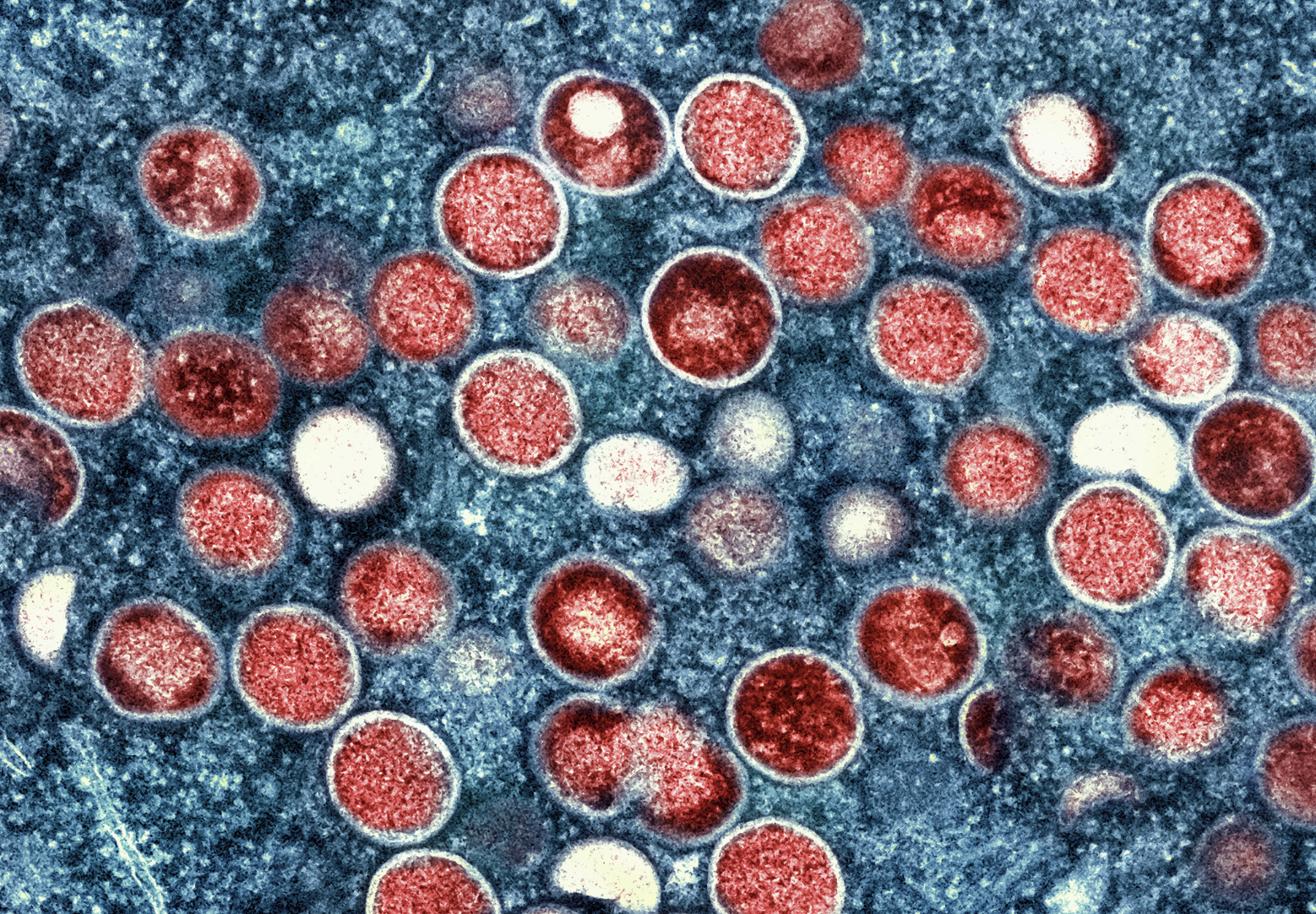

How does West Nile spread?

West Nile is spread through the bite of an infected mosquito. Mosquitoes get infected with the virus when they bite infected birds – robins and corvids, for example – who are natural hosts of the virus.

How soon do symptoms appear after being bitten by an infected mosquito?

The incubation period is relatively variable. Typically, it ranges between 2 to 14 days.

How serious is West Nile?

The vast majority of people who get infected won’t develop any symptoms. Roughly 20 per cent of people will have a flu-like symptom called West Nile fever, which is characterized by a low-grade fever and muscle aches. A small percentage of people – about 1 in 150 – will get serious symptoms, including meningitis, encephalitis or acute flaccid paralysis.

What are the common symptoms of West Nile?

In severe cases of West Nile, where the person has contracted meningitis, symptoms can include a stiff neck, severe headache, nausea, or photophobia – an extreme sensitivity to light.

With encephalitis, people may feel confused. Their level of consciousness might wane, or they might have problems with a limb. For example, they might not be able to move an arm or a leg. It appears like a stroke, but it’s a part of the infection.

Is there a vaccine or treatment for West Nile?

There is no vaccine or treatment for West Nile.

How can people reduce the risk of getting West Nile?

Adults can use a mosquito repellent that contains no more than 30% DEET. Children on the other hand should use a repellent with less than 10% DEET. Remember to use the repellent sparingly, and if you find yourself outside for an extended period of time, particularly at night when mosquitoes are most active, wear long-sleeves and pants.

Finally, mosquitoes lay their eggs in stagnant water. People can eliminate potential breeding sites around their homes by covering rainwater barrels, regularly cleaning and chlorinating swimming pools, changing the water in bird baths, and keeping eaves troughs unclogged.

NewsRelated News

News Listing

McMaster Health Sciences ➚

IIDR member and founding director Gerry Wright among McMaster professors named to Canadian Academy of Health Sciences

News

September 10, 2024

McMaster Health Sciences ➚

IIDR’s Matthew Miller and Hendrik Poinar among Health Sciences faculty recognized by Royal Society of Canada

News

September 3, 2024

August 22, 2024